Why Our Political Elite Remind Me of Dumb and Dumber

Or, the difference between the American dream and the American promise

The Kamala Harris campaign has just unveiled an “Issues” section on its website, with a striking emphasis on “opportunity.” Its first sentence says that Harris’s vision “ensures every person has the opportunity to not just get by, but to get ahead.” Its first bold heading begins, “Build an Opportunity Economy” (“where everyone has a chance to compete and a chance to succeed”). Yes, this is what a generation of campaign consultants has advised writing on your website. But does it reflect what Americans want?

One of the most consistent and counterintuitive findings in American Compass’s public opinion surveys, which we find in other survey data as well, and which we’re now beginning to understand in more depth through focus group research, is that the politically prevalent understanding of the American Dream as a chance to “get ahead” or “make it to the top” is not widely shared by the American people. To be sure, no one objects to the idea that America should be a place where anyone, wherever he starts, can achieve great things. But the obsession in our political rhetoric with “opportunity” is misplaced.

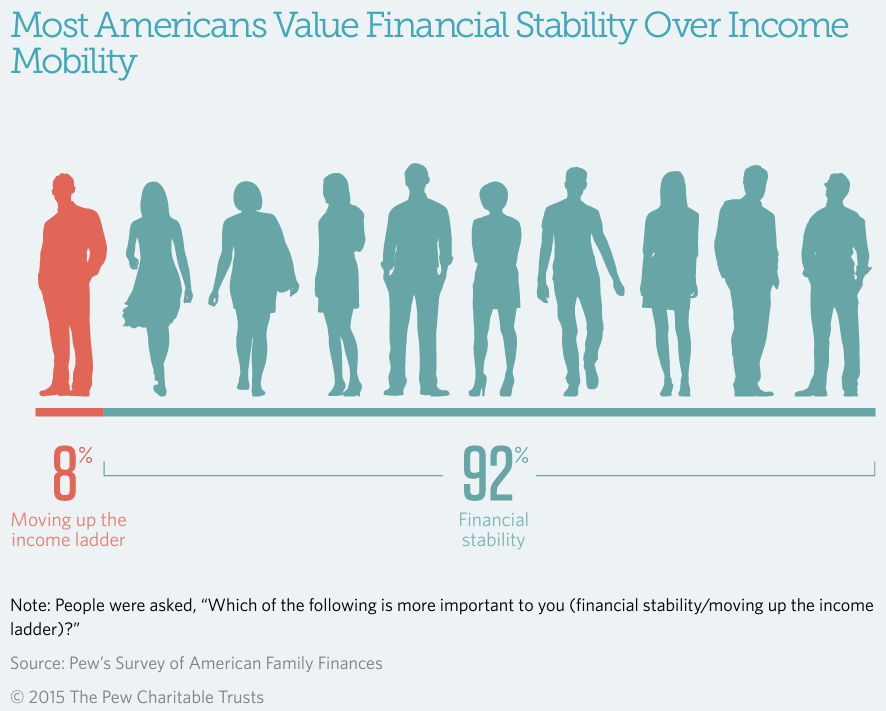

Much more important than “opportunity” and “mobility” is “stability” and “security.” I first became aware of this contrast with a fascinating question asked by Pew Research: Which of the following is more important to you: “Financial stability” or “Moving up the income ladder”?

Americans chose “financial stability” by 12 to 1, in one of the most lopsided results you’ll ever see in public polling.

As I explained in a New York Times essay in July:

While popular media often translates the American dream as being better off than your parents in materialistic terms, polling conducted by American Compass in partnership with YouGov indicates that Americans between 18 and 50 were more than twice as likely to say “earning enough to support a family” is what’s most important.

…

Note the contrast with the small cohort of upper-class Americans with college degrees and the highest incomes, who see the American dream more in terms of going as far as their talents and hard work take them than as either supporting a family or even getting married and raising children.

Likewise, in our Failing on Purpose survey on attitudes toward education, we found that:

American parents see “help students develop the skills and values needed to build decent lives in the communities where they live” as a more important purpose of the public education system than “help students maximize their academic potential and pursue admission to colleges and universities with the best possible reputations” by 71% to 29%.

For their own child, they would prefer a “3-year apprenticeship program after high school that would lead to a valuable credential and a well-paying job” over a “full-tuition scholarship to any college or university that your child was admitted to” by 57% to 43%.

They would also prefer an educational program after high school “that offers good career options close to home” over one “that offers the best possible career options but was far from home” by 56% to 44%—though, notably, upper class parents uniquely selected best-possible-career, by two to one.

In one of our focus groups, with working class Americans, we asked people to envision their ideal economy. What would it look like? Nearly every person responded with some form of “stability”; as one person put it, “a decent job that you're putting in 40 hours for and be able to not worry about making ends meet, or even affording a place to live.” No one mentioned opportunity or mobility in name or concept.

What’s going on here? I think at least three things:

First, the Odds. The obvious problem with the opportunity narrative, as framed on Harris’s website, is its speculative nature. “Everyone has a chance to compete and a chance to succeed” is a pretty good description of Hobbes’s state of nature, in which life was also nasty, brutish, and short. You know where else everyone had a chance to compete and a chance to succeed? Squid Game.

Whenever I hear the elite wax poetic about our opportunity economy, I always think of the scene in Dumb and Dumber when Jim Carrey’s Lloyd Christmas asks Mary Swanson: “What do you think the chances are of a guy like you and a girl like me ending up together?”

Mary: Well Lloyd, that's difficult to say. We really don't...

Lloyd: Hit me with it! Just give it to me straight! I came a long way just to see you Mary, just... The least you can do is level with me. What are my chances?

Mary: Not good.

Lloyd: You mean, not good like one out of a hundred?

Mary: I'd say more like one out of a million.

Lloyd: [long pause] So you're telling me there's a chance. Yeah!

Before getting excited about “a chance,” it’s important to know the odds. In America today, fewer than one-in-five young people go smoothly from high school to college to career, which both our culture and our economy have established as basically the only path to success. For men the figure is even lower. By definition, that’s an economy where “every person has the opportunity to not just get by, but to get ahead.” It’s also not one that meets many people’s expectations for America.

Second, the Baseline. Part of the problem may also be what the game theorists call the “payoff matrix.” The attractiveness of an “Opportunity Economy” depends not only on the chance of winning, but also on what you get otherwise. In an America where everyone can expect to earn a baseline and achievable level of education and then find jobs in their communities that allow them to support families, all that upward mobility and opportunity start to sound appealing. In an economy where the baseline outcome falls short of that standard and the typical worker cannot expect to achieve middle-class security, holding out the opportunity for that and more is plainly insufficient.

The Pew Research question presents financial stability and upward mobility as a dichotomy, and certainly economists and policymakers have tended to treat it as one: Sure, we have to sacrifice stability for “dynamism” and so on, we must trade off between equality and efficiency, but from their vantage point—not coincidentally, among those who have succeeded—it’s a trade worth making. A better political economy might recognize the options more in sequential terms. Opportunity and mobility are important and worthy features of a society, but they must be built atop stability and security. An economic model that takes from the foundation to build higher produces a structure doomed to fail.

Now I’m drifting far into unsubstantiated pondering, but I wonder also if this helps to explain the disconnect in our political narrative. All the focus on opportunity must have come from somewhere; it’s hard to believe generations of politicians just conjured it wrongly out of thin air. My hypothesis is that the opportunity narrative used to be much more attractive, in the 1950s–90s era when an underlying stability was present and even taken for granted. As that stability has eroded for most Americans, their enthusiasm for the chance at opportunity may have ebbed, even as the folks who win the game and find themselves in charge continue to celebrate it.

I’ve been looking for public opinion research that might prove or disprove this hypothesis, thus far to no avail. If anyone knows of published survey or focus group data from the period that bears on the question, please pass it along!

Third, the Aspiration. Finally, it’s always worth emphasizing that aspirations and definitions of the good life vary widely. The view among those who have dedicated their lives to achieving and exercising power from society’s apex tends to be a peculiar one, even as it gets broadcast from that apex as the norm. Stability and security are ends to themselves for many, perhaps most, people. And while a healthy society is one that provides and seeks to expand opportunity too, so that those who want to pursue it are free to do so, the extent of that opportunity is not necessarily what matters most. We can value opportunity and mobility without always defining them as the top priority and most worthy aspiration, making their shortcomings the key challenge, and using them as the organizing principle for our politics.

Stop to think about it, and the phrase “American dream” is a strangely ethereal one. The term itself is not from some founding national myth or document, but from a Depression-era book that defined it as “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone.” In other words, the dream is of a land that can offer to everyone a tangible promise. Most Americans seem much more concerned today with what they see as a broken promise. Defining what that promise is, understanding why we have fallen short, and finding a path to delivering on it again, is probably at the heart of a successful political message today and certainly vital to national renewal.

Oren

Thank you, Oren, for expressing humane conservative values.

This is a terrific essay.

Basically, the Scandinavians have the stability and security, and it should be no surprise that Scandinavian countries are the first, second, third, fourth, and seventh happiest countries, where the US is way down, in the 23rd place. (Israel, the Netherlands, and Norway are #s 5, 6, and 7; #s 1-4 are Finland, Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden).

People in Scandinavian countries don't have to worry about having huge medical debts wipe them out, or paying for their children's college education, or that a $400 bill will up end their lives, something that is a problem for half of all Americans.

https://www.afar.com/magazine/the-worlds-happiest-country-is-all-about-reading-coffee-and-saunas