All’s suddenly rather quiet on the tariff front. The flurry of policy announcements has slowed. Negotiations with allies are proceeding. Markets have, for the moment, stabilized. The S&P 500 has been creeping steadily upward for a week and now rests just a few percentage points below its pre–Liberation Day level, while the VIX—a measure of expected volatility—has returned to a level that would have seemed average in 2022. The yield on the 10-year treasury bond is down a bit since the President held aloft his reciprocal tariffs chart in the Rose Garden.

And then there’s China. One could be forgiven for forgetting amidst the comparative calm that the United States and China are embroiled in an unprecedented trade war, with each nation imposing tariffs of more than 100% on imports from the other. Tariffs at that level are not something either side adopted as a rational and optimal policy, rather they emerged out of escalating retaliation and counter-retaliation from which neither side is backing down—as if Dr. Strangelove had built his Doomsday Machine in a customs house. A more strategic and sustainable posture toward China is the next piece that must snap into place for the Trump administration’s efforts at remaking the international economic system to succeed.

How did we get here? By applying the same logic to China as to other trading partners, when the actual situation and objective are almost precisely the opposite. Recall, the initial reciprocal tariffs announced by President Trump were calibrated to the scale of trade imbalance with each partner and intended to force negotiations over a reconstituted alliance in which countries balance their trade with the United States and also take on greater responsibility for security. In recent remarks at the Hudson Institute, Steven Miran, chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, described the sorts of actions that the Trump administration would seek from other countries, including “they can invest in and install factories in America,” and “they can boost defense spending and procurement from the U.S.” When China responded to the reciprocal tariff not by expressing enthusiasm to negotiate, but instead with a retaliatory tariff, President Trump re-retaliated, President Xi re-re-retaliated, and here we are.

But China’s response should not have surprised or angered us. Unlike with other trading partners, we are not seeking Chinese investment in the United States, we are trying to block it. On the campaign trail, Trump did seem open to Chinese carmakers building factories here, but the thrust of his administration’s actions on trade, and its entire theory of the changing global order, assumes that China is an adversary to push away—and to demand that allies push away too. Unlike with the reciprocal tariffs devised as negotiating leverage with prospective partners, high and permanent tariffs for China were a prominent feature in the Trump campaign platform. And obviously, the United States is not looking for China to increase its defense spending and buy more American-made weapons.

So while reciprocal tariffs on other countries were intended as a starting point for negotiations, and retaliation would have represented a dismissive rebuff, in the case of China it makes no sense to understand the tariffs as a basis for negotiation at all. The plan called for them to be permanent, and of course China could and should have been expected to respond in kind. Insofar as the goal is to decouple the economies, tariffs in both directions are natural and even desirable. Escalating to levels that cause maximum immediate disruption and cost on all sides, however, is not.

The better strategy for the U.S. would be to ignore China’s actions and just adopt the policies that will facilitate the fastest possible decoupling at the lowest possible cost—what we at American Compass call the “Hard Break.” Tariffs should be one element of this strategy, but hardly the only element. For instance, more important than the explicitly temporary tariff level today is the long-term commitment to permanent tariffs that will drive investment elsewhere. To this end, the key step is revoking China’s “Permanent Normal Trade Relations” (PNTR), which requires action by Congress. Existing bipartisan legislation would take this step and impose predictable, steadily increasing tariffs on Chinese goods over time. Moving from “145% today, but with shifting exemptions, and maybe less, depending on what you do” to “steadily increasing tariffs codified in law that ensure rapid decoupling” is not a retreat, it is a maximal counteroffensive.

In addition to supply chains, the United States needs to address investment flows, winnowing both inbound Chinese investment and outbound American investment into China. The administration could take aggressive steps to bar acquisitions by China-based entities of U.S.-based assets, and deny China-based entities access to U.S.-based investors and capital markets. More aggressive export controls could bar the transfer of valuable technologies. Here, too, good legislation already available in Congress should be advanced quickly.

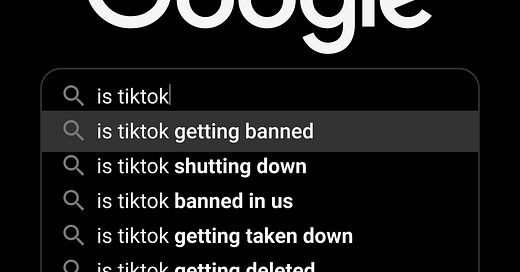

And finally, the United States can and should move to sever institutional ties between the countries. The Trump administration could protect research integrity by barring flows of funds between U.S.- and China-based institutions. It could limit access by Chinese nationals to U.S. universities. Congress could block U.S.-based media and entertainment companies from generating revenue in China, eliminating the incentive to self-censor for the benefit of the CCP. And of course, Congress has already mandated the shutdown of TikTok. Shut it down.

President Trump should announce that the Liberation Day tariffs were China’s last opportunity to indicate any willingness to reconsider its exploitation of the global economic system, and that it is now obvious that no deal is possible. Thus, the United States is moving away from a negotiating posture and toward one focused on permanently disentangling the two economies at the lowest possible cost to the American people. He should urge Congress to move forward with its PNTR legislation, which would impose tariffs on strategic goods that increase steadily toward 100% over five years; in the interim, he should align his own tariffs with that schedule. He should take the other executive actions he can and ask Congress to make permanent the investment and institutional provisions as well.

And then, as importantly, he should initiate a crash program in developing alternatives for those critical supply chains like pharmaceutical ingredients and critical minerals where China’s position in fact poses a short-term security threat. The Defense Production Act was designed for, and is perfectly suited to, doing just that.

How would China respond? It could maintain its own high tariffs regardless of the United States action, but why would it? China is not trying to protect or reshore production, or relocate its supply chains. It could be trying to deny American producers access to its market, which it largely already has, but doing so would only advance the policy to which the United States is committed anyway. The more likely outcome is that both countries accept the inevitable decoupling and adopt the pathways that impose minimal cost on their own populations.

President Trump has already shown that he is willing to make course corrections as the responses to his actions materialize. He paused the reciprocal tariffs to allow time for negotiation, and by all indications he is glad that he did. With a recalibration on China, the Liberation Day agenda would come much closer to maximizing the return on the investment that he is asking Americans to make.

- Oren

He could absolutely do this.

Unfortunately, he is entirely too stupid to do this. Also, he doesn't really care about any of it. He just wants China to kiss his ring.

It's all he's ever cared about.

The tariffs are not “reciprocal.” They were unilaterally imposed by Trump. That makes a rational discussion of preferred U.S. trade policies going forward more difficult. Walling ourselves off from China is a questionable policy choice. Our 330,000,000 population is about a third of their one billion population. Their consumer middle class continues to grow. They already excel in manufacturing EVs, solar panels, and more. We need to figure out how to trade with them to our mutual benefit. Focusing on trade, not military capabilities makes sense in the long run for both countries. While reaching a deal is not in any way a certain outcome, win-win negations are the best path forward for both countries. We should be in a position to clearly communicate our negotiating positions. The chaotic Trump administration has so far been entirely incapable of performing that task. Doing so would require them to take into consideration the views of corporate leaders and, at least, middle of the road Democratic Party leaders, if we are to re-set our trade policy with a life-span beyond the next few years.